AIA UK Student Charrette: Reimagining the Strand Aldwych After Dark

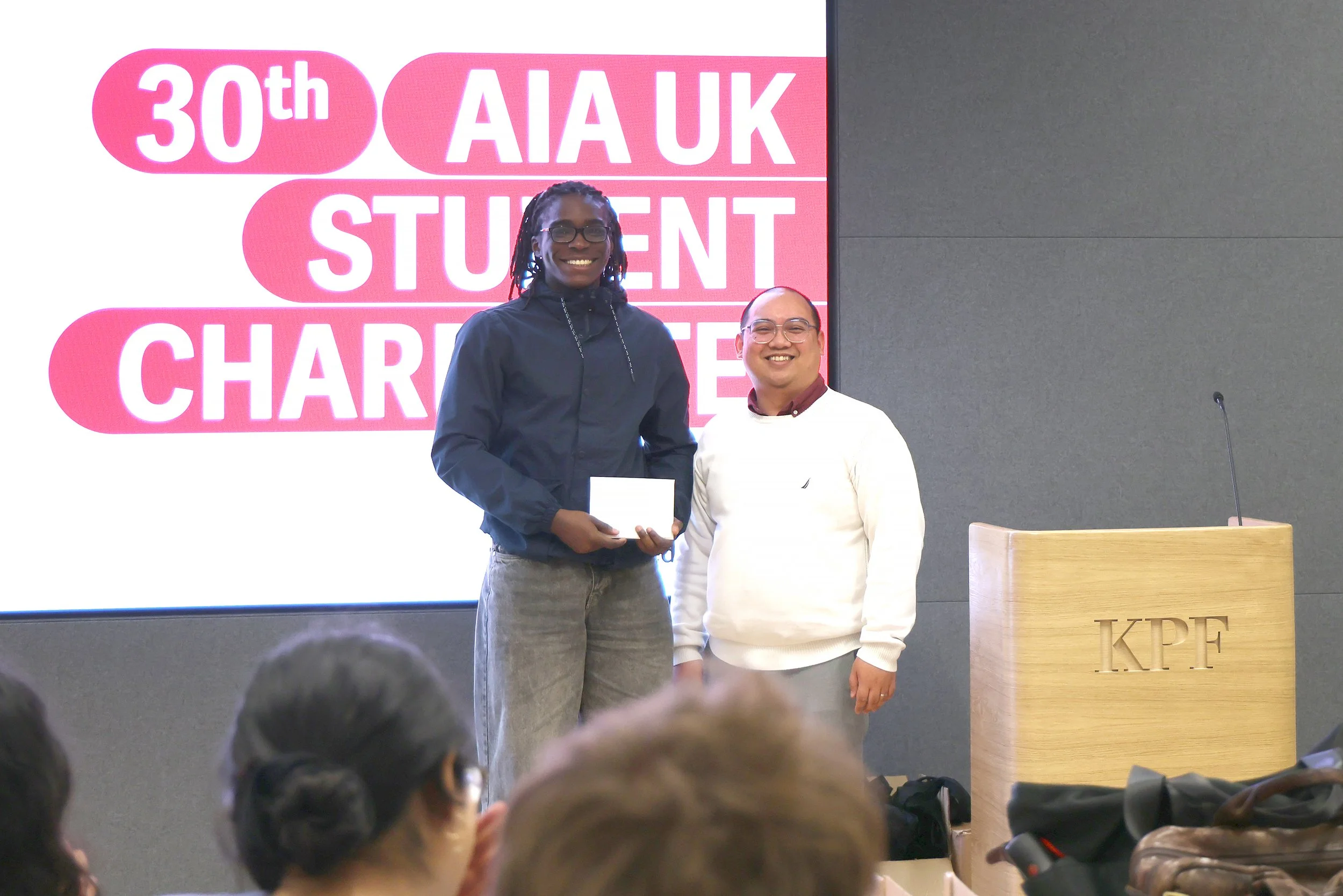

On November 8, 2025, the Kohn Pedersen Fox (KPF) gallery in London transformed into a dynamic workshop of ideas for the 30th edition of the AIA UK Student Charrette. For the third consecutive year, KPF opened its doors to sponsor and host the jubilee event, welcoming over 60 Part I architecture students from 13 universities across the UK to tackle one of London's most pressing urban challenges: designing for public space after dark.

The day-long design sprint challenged emerging architects to reimagine the Strand Aldwych area as part of Westminster's After Dark Strategy 2040, addressing critical issues of safety, accessibility, cultural vitality, and sustainability in the capital's nighttime economy.

A Brief for the Future

Following a welcoming breakfast reception that fostered connections between students, mentors, and jurors, Siyu Zhao of AIA UK unveiled this year's provocative brief: "Design for Public Space After Dark." The challenge tasked participants with transforming the Strand Aldwych—a historic thoroughfare steeped in cultural significance—into a vibrant nighttime destination that supports community engagement, cultural enrichment, and the physical and mental well-being of Londoners.

The brief responded to Westminster's ambitious 2040 strategy, which seeks to diversify night-time activities beyond traditional hospitality venues while maintaining the area's unique character and ensuring resilience and sustainability for future generations.

From Observation to Innovation

Armed with cameras and sketchbooks, student teams ventured into the streets of Strand Aldwych alongside their mentors, documenting the site's physical fabric, circulation patterns, and social dynamics. This immersive site analysis phase proved crucial, as teams observed firsthand how the historic district's character shifts dramatically between day and night.

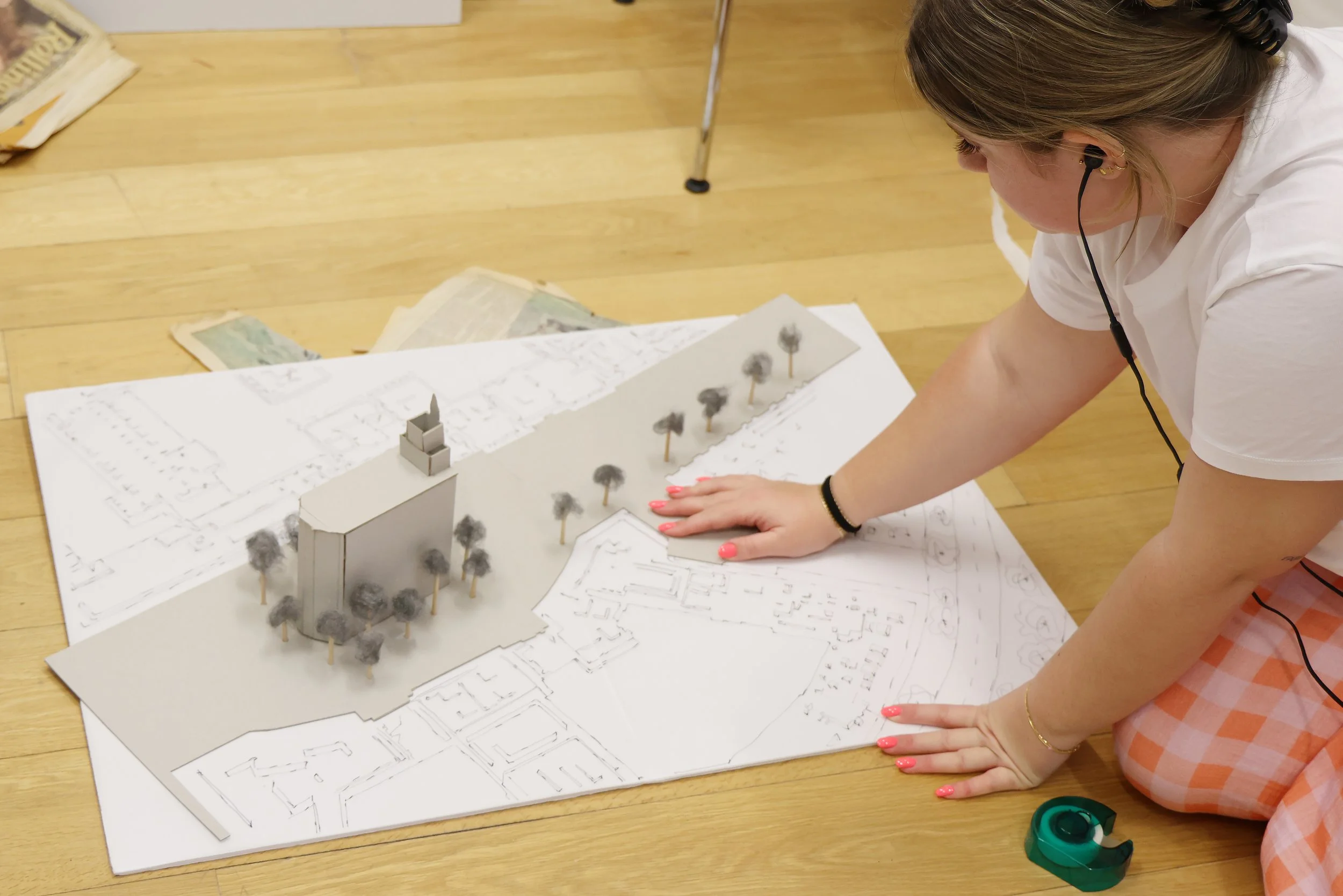

Returning to the KPF gallery, the real challenge began: a 4.5-hour analogue design sprint. In an era dominated by digital tools, the charrette embraced a CAD-free approach, pushing students to express their ideas through hand-drawn plans, sketches, and physical models. This constraint fostered spontaneity, collaboration, and a raw creativity that digital workflows often constrain.

Diverse Visions, Shared Values

The afternoon culminated in presentations to a distinguished jury comprising Michelle Ludik from ADAM Architecture, Stephen Drew from Architecture Social, and Samantha Cooke from KPF. Each team's proposal demonstrated sophisticated understanding of the site's layered history and cultural significance, while offering bold visions for its nighttime transformation.

The jury praised the breadth of approaches, noting how students integrated public engagement strategies, inclusive design principles, and sustainable interventions into their proposals. From illuminated pedestrian networks to pop-up cultural programming, the designs reflected a generation of architects attuned to the social dimensions of urban space.

Celebrating Excellence

After thorough deliberation, the jury announced its winners:

First Place: Group 2

Students from Sheffield Hallam University, University of Kent, and University of Greenwich, mentored by Pierre Baillargeon, claimed top honours. Their proposal distinguished itself through a seamless integration of community engagement, environmental sustainability, and contextual sensitivity—demonstrating how nighttime activation can enhance rather than compromise a historic district's character.

The winning team mentored by Pierre Baillargeon, AIA, NCARB, ARB, RIBA: Students from Sheffield Hallam University, University of Kent, and University of Greenwich: Aneeqa Hussain, Bea Barros, Riya Riya, Taqwa Elmrom, Ekaterina Andonova, Lucien Percy, Fatoumatta Ndure.

First Runner-Up: Group 8

A collaborative team from the University of Greenwich, University of Hertfordshire, and University of Westminster, guided by mentor Laura Petruso, earned recognition for their innovative approach to inclusive nighttime programming.

The 1st runner-up team mentored by Laura Petruso, AIA, ARB, OAC: Students from University of Greenwich, University of Hertfordshire and University of Westminster: Lamis Sami, David Akala, Abdulatif Ghani, Ayub Abdulkadir, Einas Heidari, Gamid Aliev, Sajida Akther.

Second Runner-Up: Group 6

Students from the University of Greenwich, mentored by Francis Hur, rounded out the podium with a compelling vision that balanced historical preservation with contemporary urban needs.

The 2nd runner-up team mentored by Francis Hur, AIA. Students from University of Greenwich:Alexander Ojejinmi, Firdowsun Nahar, Jaewoo Oh, Jessica Tirira Quezada, Jordan Jatto, Kaliah Henry, Madiha Payman, Sophia Tsui.

Celebrating 30 Years: Special Individual Awards

In honour of the 30th anniversary milestone, AIA UK introduced special individual recognition awards celebrating exceptional contributions throughout the day:

Early Bird Award: David Akala (University of Hertfordshire)

David arrived first and set a focused, energetic tone for the entire event. His early commitment and readiness to engage demonstrated the dedication that would characterize the day's collaborative spirit.

David Akala (University of Hertfordshire)

Presenters of the Year: Iain McCallum (University of Dundee) and Veronika Austin (University of Greenwich)

Both recipients delivered clear, structured presentations that captivated the jury and kept the room fully engaged. Their confidence and precision in communicating complex design ideas exemplified the communication skills essential to architectural practice.

Iain McCallum (University of Dundee)

Veronika Austin (University of Greenwich)

Most Immersed Award: Sobhia Boularas (University of Hertfordshire)

Sobhia remained fully absorbed in her craft from start to finish, demonstrating steady concentration and an unwavering drive to refine every detail of her model. Her dedication embodied the focused intensity that defines exceptional design work.

Sobhia Boularas (University of Hertfordshire)

The Power of Mentorship and Collaboration

AIA UK extends heartfelt gratitude to the mentors who played an instrumental role in the charrette's success. Their expertise and guidance were essential in shepherding students through each phase of the design process, from initial site analysis through final presentation.

The event's success also depended on the dedication of its organizers and volunteers, including Paolo Mendoza from Benoy, Rishi Lal from HOK, and Siyu Zhao from ADAM Architecture. Special recognition goes to the volunteers from KPF London—Marcela Manole, Cristina Mock, Carolyn Ardaiz, Gaëlle Brohard, and Anna Mytcul—whose behind-the-scenes work ensured the day ran seamlessly.

Looking Forward: Analog Design in the Age of AI

The 30th AIA UK Student Charrette proved especially meaningful in an era increasingly shaped by artificial intelligence and digital automation. By requiring hand-drawn work and physical model-making, the event reminded participants of the irreplaceable value of tactile exploration, spontaneous sketching, and direct material engagement in the design process.

"This event was very special for AIA UK and for the students," organizers noted. "We are motivated to continue this tradition and deliver amazing results through many more upcoming years."

As London grapples with the evolution of its nighttime economy—balancing safety concerns, cultural vitality, and residential quality of life—events like the AIA UK Student Charrette demonstrate how emerging architects can contribute fresh perspectives to longstanding urban challenges. The proposals generated on November 8 may be student projects, but the questions they address are urgently real: How do we create public spaces that serve diverse communities around the clock? How can design foster safety without surveillance? How might historic districts embrace contemporary nightlife while preserving their character?

The 30th charrette proved that the future of London's public realm is in capable, creative hands.

Project Credits:

● Event Organizer: AIA UK

● Host & Sponsor: Kohn Pedersen Fox (KPF)

● Brief Coordinator: Siyu Zhao, AIA UK

● Jury: Michelle Ludik (ADAM Architecture), Stephen Drew (Architecture Social), Samantha Cooke (KPF)

● Organizers & Volunteers: Paolo Mendoza (Benoy), Rishi Lal (HOK), Siyu Zhao (ADAM Architecture)

● KPF London Volunteers: Marcela Manole, Cristina Mock, Carolyn Ardaiz, Gaëlle Brohard, Anna Mytcul, Jamar Rock.

● Participants: 60+ Part I architecture students from 13 UK universities

● Date: November 8, 2025

● Location: KPF Gallery, London

Special thanks to KPF for their continued support of architectural education and their generous provision of gallery space for this milestone event.

Written by Anna Mytcul, Associate AIA

Photos by Cristina Mock, Associate AIA

Volunteer with Architects Climate Action Network (ACAN!)

New AIAUK Volunteering Initiative

AIA UK is all about building community, and so we're delighted to announce that we're starting a program of collaborative volunteering initiatives for you to get involved in a variety of new communities, in and outside of the architectural world.

We are delighted to kick-off this initiative by collaborating with the Architects Climate Action Network (ACAN!), starting with a series of youth sustainability workshops - combining two key focus areas of AIAUK of climate action and student support. ACAN! is a dynamic network of architecture and built environment professionals dedicated to addressing the climate and ecological crises through activism, education, and systemic change. Together, we will help deliver engaging workshops that introduce children to key sustainability themes using creative, hands-on projects. The first workshop, titled "Introduction to Circularity" will take place on December 14th, marking the start of an inspiring journey to empower young minds to shape a resilient and caring future. For further information please register your interest here.

We are also very pleased to be collaborating with the Ukraine Arts Hub on their work providing creative art classes for Ukrainian refugee children.

Details of all our upcoming volunteering opportunities will be automatically emailed to all members. Our new Director of Volunteering Kristy Sels is developing our program of collaborations over the coming months, so do please get in touch with her directly at volunteering@aiauk.org with ideas and opportunities to share.

Architects’ Action for Affordable Housing Commitment

New AIAUK Commitment

AIAUK is proud to be a values-based organisation. We seek to meaningfully support activities that align with our values, and sign-up to commitments which can make a difference. For example, we were a foundational signatory to the 1.5oC Climate Actions Communique. We are delighted to announce that we agreed in 2025 as an organisation to sign up to the Architects' Action for Affordable Housing, an issue of pressing urgency both in the UK and globally, and in which architects must play a key role.

If you are an AIAUK member with a cause or commitment that you believe we should consider signing-up to, please contact us directly with further details.

2025 Membership Survey Results

Thank you for taking the time to complete our member feedback survey. Your input is incredibly valuable in helping us shape our programming so that it is more engaging, accessible, inclusive, and relevant to your professional interests and membership experience. This survey is part of our ongoing effort to better understand our community's needs and foster a more diverse and connected architectural network. We have reviewed your responses and will be using your feedback below to inform our 2026 event programming—including new themes, formats, initiatives etc.

Key Takeaways (overall picture)

Members appreciate high-quality, varied events and networking opportunities, especially when offered online.

There are concerns about London-centric focus, high dues (particularly national), and scheduling issues.

Members want AIA UK to expand reach, increase advocacy, and provide more practical/skills-based offerings.

Strengths (what AIA UK is doing well)

Event quality & variety: Positive feedback on sustainability events, collaborations with RIBA, and online sessions.

Networking/community: Members value connections made through AIA UK.

Accessibility: Online/hybrid events allow broader participation.

Membership value (for some): Tax relief and event offerings make dues worthwhile for engaged members.

Recognition of efforts: Volunteers and the chapter team were appreciated.

Areas to Improve (what needs attention)

Geographical reach: Reduce London-centricity; more regional, hybrid, and online events.

Content & format: More networking/social events, skills workshops (business, data, tech), virtual project tours, and content with stronger professional relevance.

Scheduling & notice: Minimum one month’s notice, alignment with school holidays, and activity options in December.

Cost & accessibility: Excursions too expensive for some; dues (especially national) seen as poor value by those outside the US or with financial constraints.

Advocacy & collaboration: Stronger voice on climate/built environment issues; deeper collaboration with RIBA/ARB; consider lobbying.

Membership experience: Better communication, improved membership directory, legislative alerts, and website functionality.

A Call to Action

As many of you may know, ALL of the chapter programming is organised and run by members who volunteer their time to give back to this growing community. To implement the changes you want, we need your help.

In particular, for additional geographic reach to augment our UK-wide offering, we need members across the country to get in touch and help organise an events near you. Please email chapterexecutive@aiauk.org. We look forward to hearing from you!

Written by Lulu Yang, Assoc AIA

Continental Europe Madrid 2025 Conference / Reimagining Madrid

Madrid as seen from the IE University Tower, School of Architecture. Photo Credit: L King AIA

Veteran AIA UK Members are by now fully aware that AIA Continental Europe’s biannual conferences offer excellent opportunities for travel, camaraderie and architectural adventure (as well as abundant Continuing Education Units!). Indeed, many UK members attended the joint AIA UK/AIA CE Conference in Cork last Spring and are now thoroughly familiar with CE’s basic format of lectures and tours generously interspersed with fun and food.

However, conference attendance should not be written off as a seen-one-seen-them-all experience. This year’s Madrid Conference offered an altogether distinctive atmosphere from Cork and no doubt Berlin will also highlight its own distinctive atmosphere in Spring 2026. AIA UK members are urged to take every opportunity to visit European cities via AIA CE’s expertise. Learn more about AIA CE’s past and future events HERE.

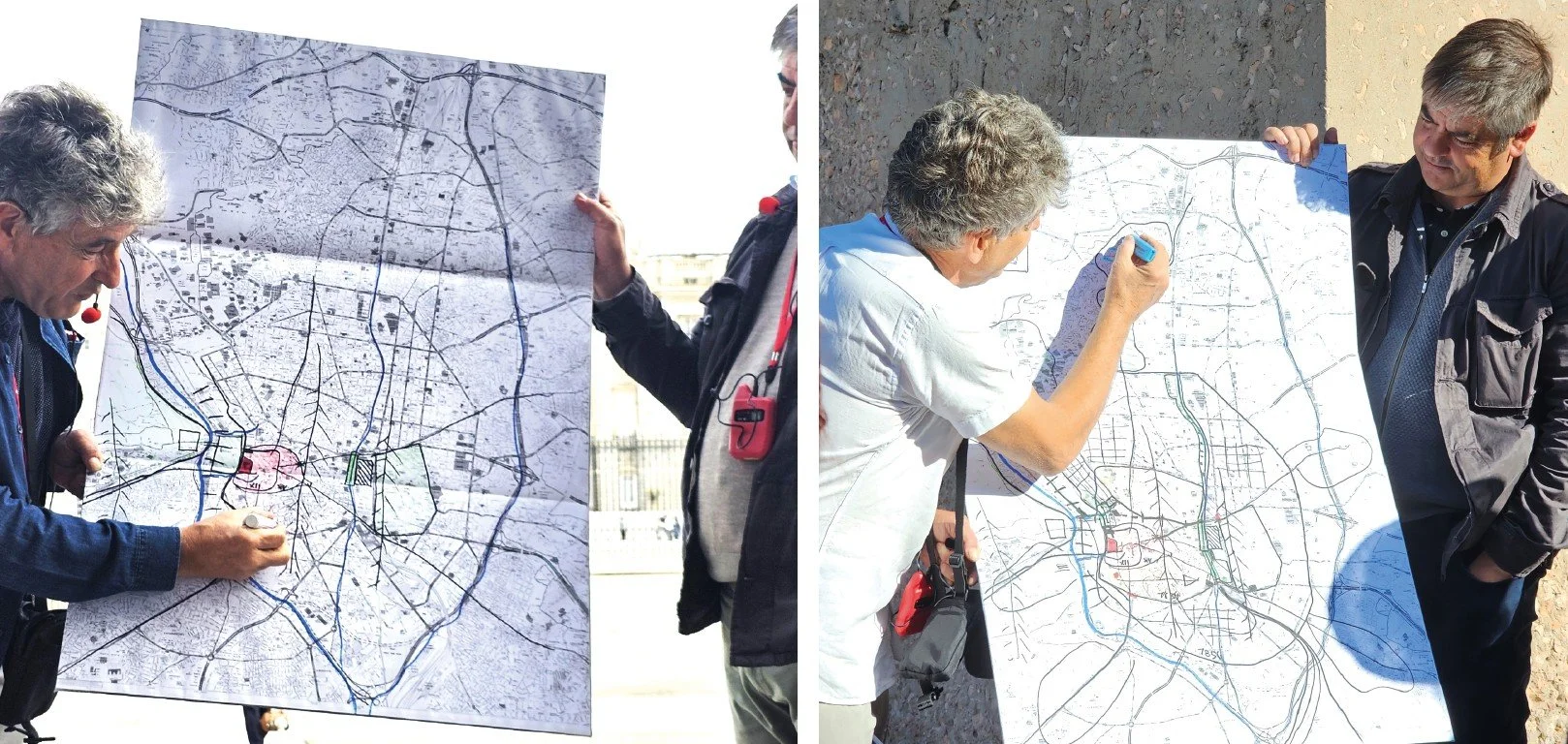

Instead of using a fixed conference venue for a series of pertinent lectures as have other CE conferences, the Madrid organisers engaged two enthusiastic, peripatetic architects to explain the city. Werner Durrer and Ivan de Alma shared their knowledge of Madrid through on-the-spot, in-person storytelling against a living backdrop.

Beginning with a clean map, Werner’s hand-drawn annotations gradually traced Madrid’s growth through the centuries as the conference moved across the city. This novel approach gave conference attendees a sense of intimacy as they celebrated Madrid’s amazing neighbourhoods and distinctive buildings.

The brief outline below touches on highlights only of the conference. A fuller, more detailed itinerary with dates can be found HERE. A speaker list can be found HERE. A Google Map overview of the city can be found HERE.

Friday, 16 October The first day was one of initial discovery of Madrid’s traditional architecture interspersed with unusual interventions. It began early with a pre-opening-hours tour of the Escuelas Pías Library and a discussion about the urban regeneration of the Lavapiés neighbourhood.

Escuelas Pias Library and Lavapiés housing. Photo Credits (left to right): RD Reber AIA and L King AIA.

The church, destroyed during the Spanish Civil War, remained in ruins until 2004 when it was converted into a spectacular library. The new plaza in front of the church exposed the courtyard façade of a traditional building block, offering insight into the city’s basic housing form.

A walking tour through the historic core of Madrid began at the Royal Palace and continued to the Plaza Mayor. Along the way, the group admired the mix of Arabic and Spanish architectural influences, characterised by grey granite and red brick facades. Side visits included the recently renovated Iván de Vargas Library and the Mercado San Miguel.

As the group progressed toward the Gran Vía, the architecture morphed from the 16th Century to more modern times, culminating with several grand buildings from the early 20th Century clustered around the Plaza de Cibeles. Lunch was provided at the Azotea restaurant atop the Círculo de Bellas Artes building, with fantastic views over the city.

The view from the Azotea Restaurant. Photo Credit: RD Reber AIA

After lunch, the group visited the Joaquín Leguina Regional Library and Archive in the former El Águila brewery, followed by a thought provoking roundtable at AECOM’s Madrid office titled ‘Reimagining Madrid’. The day concluded with a lively and generous cocktail reception on AECOM’s rooftop terrace.

Saturday, 17 October The 2nd day was again packed with contrasting sights of traditional cityscapes and modern buildings. The tour started at the Plaza de España with an explanation of how the plaza – with its landscaped gardens and memorials – sits over tunnels that were only recently constructed to contain sections of Madrid’s traffic system underground.

It then transversed the city by bus to chart urban development since the 19th century. Modern interventions within traditional contexts included the Museo ABC, the Mercado de Barceló, and the BBVA Tower.

The striking Corten façade of the BBVA Tower contrasts with the geometric shapes of the Museo ABC. Photo Credits: L King AIA

Away from the central Madrid, the bus travelled far north to visit the Cuatro Torres business park with its quartet of high-rise buildings that have become a city landmark. A tour of the IE University Tower showed how it had been designed to incorporate an unexpected “vertical campus” for their School of Architecture. IE’s faculty gave an absorbing lecture on contemporary Madrid planning issues, ‘The Profound Transformation of Madrid,’ outlining the ambitious plans – including a high speed rail terminal - for the immediate neighbourhood.

After lunch at the IE Tower, the bus returned past other notable buildings, including the bizarrely leaning KIO Towers and the Santiago Bernabéu football stadium. A stop at the 1930s Hipódromo de la Zarzuela revealed a spectacularly thin, cantilevered concrete roof over the racetrack’s grandstands.

The day’s touring finished on foot with a guided tour of the Madrid Río Park, a monumental infrastructure and landscape project, built over tunnels adjacent to and under Madrid’s Manzanares river. The landscape architect who led the team, Christian Dobrick of West 8, explained how the project - which involved multiple contractors and government departments as well as tough interfaces with existing infrastructure - was completed in record time under intense political pressure.

Keeping with the long-standing AIA CE tradition of Saturday night conference dinners, cocktails and dinner were enjoyed at the Posada de la Villa, a restaurant in the old town whose on-view, speciality oven - if not the whole building – dated back to 1642.

Sunday, 18 October The third day returned to central Madrid for a visit to the very modern interior spaces of the National Archaeological Museum, where the architect who oversaw the renovations, Jorge Rodriguez, led a tour highlighting how the design team and museum staff worked together to enhance the exhibits.

The group enjoyed a coffee break in the beautiful Retiro Park before proceeding to the 1949 Rationalist masterpiece, the Ministry of Health building, and the Reina Sofía Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art. Lunch was held on the top floor of Herzog & de Meuron’s Caixa Forum, adjacent to a ‘vertical garden’ wall that appears to defy gravity.

Defying gravity at the Caixa Forum. Photo Credit: RD Reber AIA

Monday, 20 October The traditional Extension Day for those able to stay in Madrid longer focused on Segovia and its breathtaking Roman Aqueduct before touring IE’s newly expanded ‘Creative Campus’ housed in a sensitively renovated medieval building.

The Segovia viaduct and IE’s ‘Creative’ Campus. Photo Credits: RD Reber AIA

No conference could finish without another fabulous meal, so the group proceeded to the renowned Mesón de José María restaurant, where they took part in the ceremonial carving of a suckling pig, which involves using the edge of a plate, rather than a knife, to demonstrate how tender the meat is. It was joyous conclusion to a fabulous conference!

The 2025 Madrid Conference was well organised - a conference without a hitch!!! - by Sophia Gruzdys AIA. Irene Reidy – CE’s Chapter Administrator - managed the administration with volunteer help from her partner, Liam Quinn.

Corporate partners for the conference included:

Roca/Laufen, panoramah!, IE University School of Architecture and Design, AECOM, Miller Knoll and Frener Reifer.

Sophia Gruzdys AIA and Irene Reidy on the job. Liam Quinn consulting with an anonymous helper re tour headsets.

Written by L King, AIA and RD Reber, AIA

My MRA Experience: Etain Fitzpatrick on Perseverance

When I arrived in London, 20 years ago, the thought of becoming a qualified UK architect was the last thing on my mind. I had arrived onto an extremely busy project and was only meant to be here for six months and anyway I was already a registered architect in the state of New York.

However, fast forward seven years later, I was still in London and had decided that, as Lord Kitchener sang in the calypso classic, ‘London is the place for me’! I wanted to remain long-term and not being able to call myself an ‘architect’ in the UK while I was designing and delivering significant projects in London was frustrating, to say the least.

In 2014, I tried to get my Part 1 through the ARB Prescribed Examination process and for various reasons, ultimately, I failed. I was devastated, not only was it a humiliating experience, it was also very expensive! However, that didn’t deter me, I decided to get my Part 3 qualification. The course would help me with some of the evidence required for the prescribed examination and was ultimately required to obtain my UK qualification. I signed up for a Part 3 course at London Metropolitan University and I received my Postgraduate Certificate - Professional Practice in Architecture with Merit in 2015. Success!

Now back to the Part 1 prescribed examination….In 2017 I decided to take ‘Preparing for the ARB Prescribed Examination’, a short course at the University of Westminster. Yes, the prescribed examination is so complicated that there are courses to explain it. After the course, well, I procrastinated. I could never find the motivation to start the process for the Part 1 prescribed examination again.

In 2023, there was a glimmer of hope. The only good thing to come out of Brexit, a Mutual Recognition Agreement (MRA) between the UK and US architects was announced, at last! Hosted at the RIBA, leaders from RIBA, ARB and NCARB held a presentation followed by question and answers about the new agreement. I was buoyed! However, they were talking about requiring a UK Adaptation Assessment and I had my Part 3 qualification. I asked if I could use that in lieu of the assessment, but that ARB didn’t have an answer at that time. I followed up with the ARB by email afterwards and they said they were to discuss it at their next Board Meeting. I followed up again a few months later and the ARB confirmed that I could use my Part 3 qualifications in lieu of doing the UK Adaptation Assessment. I was one step closer….

However, another issue came up, New York State, where I am registered, was not participating in the MRA. Apparently, they were concerned about getting a surge of UK architects to NYC. Therefore, I needed to become licensed in a participating State. I reinstated my NCARB certification, became a licensed architect in the State of Pennsylvania (which included getting a set of fingerprints done for an FBI background check) then I used that license to apply for qualification at the ARB. The ARB then sent me a link to start my UK Adaptation Assessment, however, I informed them that I had my Part 3 qualification, which was fine, except, because I had received it over two years ago, I needed to submit my job description, a letter stating why I wanted to join the ARB register and list of two years of CPD. I submitted all the above and then in February 2025 I finally received my ARB registration certificate. After 20 years of working in the UK. I could finally call myself an Architect.

I need to run now, the first year of my ARB registration is due for renewal and I need to record my CPD. Cheerio!

Etain Fitzpatrick AIA NCARB RIBA ARB, a Director at JRA and is based at their headquarters in Southwark, London.

Written by Etain Fitzpatrick, AIA NCARB RIBA ARB